This morning starts 144 consecutive days of exploring the symphonic works of Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896).

This morning starts 144 consecutive days of exploring the symphonic works of Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896).

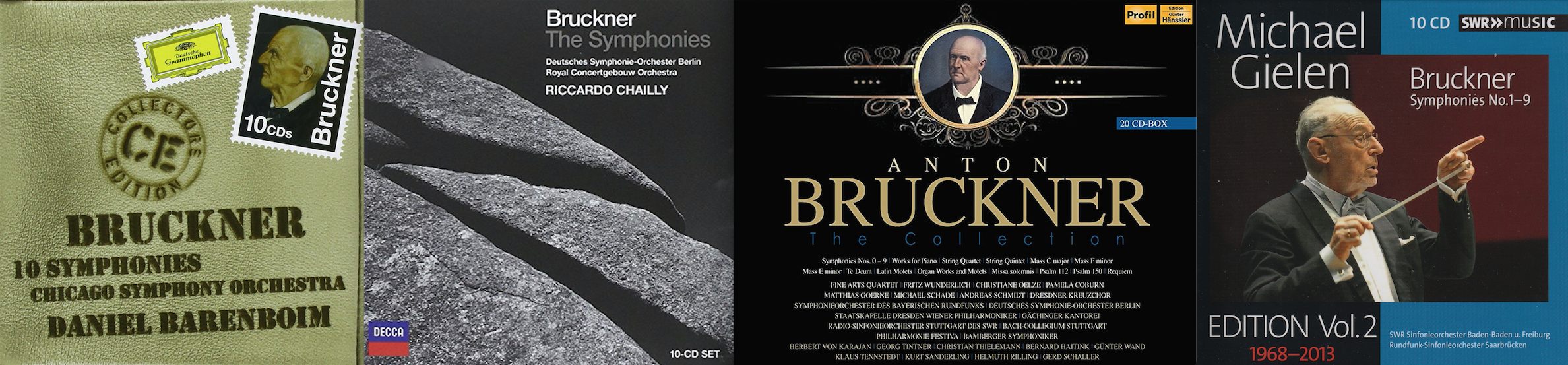

It’s 144 days because there are nine symphonies and 16 box sets (9×16=144), representing some 14-17 different conductors who recorded Bruckner over the last 50-60 years in venues around the world.

I decided to listen to the symphonies in alphabetical order by conductor. That seemed easier than trying to figure out chronological order of when the symphonies were recorded, or some other esoteric method.

I decided to listen to the symphonies in alphabetical order by conductor. That seemed easier than trying to figure out chronological order of when the symphonies were recorded, or some other esoteric method.

Given that, today’s conductor is Argentine-born Daniel Barenboim (1942-), who is also a renowned pianist. Here is his official YouTube channel.

Barenboim’s rendering of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (the 1866 “Linz” version) was recorded in December of 1980 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Bruckner was 41 when he wrote this symphony. Barenboim was 38 when he conducted it.

By the way, even though I’m listening to nine symphonies, Bruckner wrote two others, which are classified and categorized (along with all his works) under a system called WAB, an acronym that stands for Werkverzeichnis Anton Bruckner. (Werkverzeichnis is German for “catalog of works.”)

Symphony No. 1 is WAB 101.

Bruckner’s other two symphonies are referred to as “Study Symphony” (WAB 99), and Symphony in D Minor (WAB 100), respectively. It’s worth clicking on the links to read about those works. For example, I found it interesting that WAB 100 was actually written between WAB 101 and WAB 102, not prior to WAB 101.

According to the Wiki entry,

In 1895 Bruckner declared that this symphony “gilt nicht” (does not count) and he did not assign a number to it. The work was published and premiered in 1924.

The way I look at it, if Bruckner, himself, did not want WAB 100 included among his other symphonies, why include it among his other symphonies? I’m a purist that way.

Plus, I did not want to include symphonies WAB 99 and WAB 100 in my project for another, far more practical reason: They are rare, and far fewer box sets contain them.

So I chose to focus on the nine symphonies that are easier to obtain, especially in complete box sets. After a lot of searching, and a couple of months obtaining, I found 16 such box sets.

Which brings me back to the Barenboim set and Symphony 1.

From the first paragraph of the excellent liner notes in this box set:

For many people, Bruckner is the composer tho developed and perfected the post-Beethoven symphony as a coherent form by exploiting its possibilities to the full, while for those other listeners who simply do not know where to begin to make sense of his large-scale symphonic structures, he remains an eccentric, a late developer and a provincial figure dismissed by Strauss in a famous witticism: “This is how peasants compose in our country.”

Seems a little harsh to me.

If I were a peasant, I’d give my only donkey (well, what else do peasants have to give?) to be able to compose like this.

Besides, I’d rather hear Bruckner than Strauss any day.

Take that, Johann!

Or was it Richard?

I can’t find that quote online, attributed to any Strauss, Richard or Johann. Also, I looked through four relatively hard-to-obtain books about Bruckner and I couldn’t find that quote in them, either.

Still, it doesn’t sound far afield. From what little I know of Bruckner he was harshly criticized in his lifetime. For more about Bruckner and his life, see my Anton Bruckner page.

It is worth noting that, according to the CD liner notes, “…there are nine numbered symphonies, whereas Bruckner actually wrote at a total of eighteen.”

According to the book The Essence of Bruckner by Robert Simpson,

There are two authentic versions of the official No. I. The original score dates from 1865/6 and the later revision, by Bruckner himself, was carried out in 1890/1 (Vienna). There are no fundamental changes in the structure; the basic shape remains the same in the revision, odd bars being dropped or added here and there, unhappily squaring the phrase-rhythms. But there is a great deal of re-working over details, and passages are actually re-composed. The Vienna score is rarely an improvement over the original, and often the simplicity and urgency of Bruckner’s inspiration in Linz is ruined by fussy and frequent detail. The revision betrays the composer’s nervousness and perhaps his state of health. (p. 29)

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 1, the 1866 Linz version), from this particular conductor (Barenboim) and this particular orchestra (Chicago Symphony Orchestra), is as follows:

Allegro…………..12:19

Adagio……………12:12

Scherzo……………9:06

Finale……………..13:28

As a reminder, here is what each term means (first two from the Wikipedia article):

Allegro = joyful; lively and fast. Moderately fast.

Adagio = ad agio, at ease. Slow, but not as slow as largo.

Scherzo = The word “scherzo,” meaning “I joke,” “I jest,” or “I play” in Italian, is a piece of music, often a movement from a larger piece such as a symphony or a sonata, often in 3/4 time. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often refers to a movement that replaces the minuet as the third movement in a four-movement work, such as a symphony, sonata, or string quartet. Scherzo also frequently refers to a fast-moving humorous composition that may or may not be part of a larger work.

Finale = the last movement of a sonata, symphony, or concerto; the ending of a piece of non-vocal classical music which has several movements; or, a prolonged final sequence at the end of an act of an opera or work of musical theatre.

In Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1…

Allegro begins with a slow fade up that sounds like the chugging of a train climbing a low hill. It builds and then bursts forth in triumphant fashion, laying back again and starting the chugging.

From what I remember of listening to Bruckner before today, he uses a lot of repetition, symmetry, in his compositions. Repeated phrases. Almost like hooks in a pop song today.

Adagio does what an adagio does – retards the pace, slows things up to let the theme expand. It’s a pretty piece of music.

Scherzo leaps from the chute like a racehorse raring to run. The melody reminds me of the theme song to Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot TV series. That’s crazy, I know. The instruments aren’t even the same. But it’s reminiscent of that theme, at least to my untrained ears.

Here. Listen for yourself:

Barenboim’s Symphony No. 1, Movement Three Scherzo.

Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot theme song.

Now, tell me. Don’t those sound similar to you?

Finale – a strong finish with lots of flourish.

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 4

CD liner notes: 5

How does this make me feel: 4

Symphony No. 1 is a stirring, pleasant experience. It’s not as gripping to me as, say, Symphony No. 8, or even one of Beethoven’s symphonies. But it has what it takes to arrest and hold my attention from start to finish. And isn’t that all we can ask of a piece of music?

As luck (providence? fate? coincidence?) would have it, when I researched Daniel Barenboim, I discovered he’s conducting a series of concerts at Carnegie Hall.

By chance, I clicked on the listing for January 28th…

…and discovered Barenboim will conduct Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 during the very week in my Bruckner schedule in which I’ll be listening to Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8, anyway. What are the odds of that?

It’s my favorite Bruckner symphony, too.

That kind of providential match up I could not possibly ignore.

So, I just bought tickets.

The orchestra will be Staatskapelle Berlin, the orchestra of the Berlin State Opera (Berliner Staatsoper Unter den Linden).

Cool.