This morning begins the final leg of my 144-day exploration of the nine major symphonies Bruckner wrote.

However, on Day 145 I will do something I didn’t originally plan to do – go back to Symphony No. 1, with seven more conductors from seven additional CD box sets that I had omitted (intentionally or inadvertently) when I put together my 144-day project.

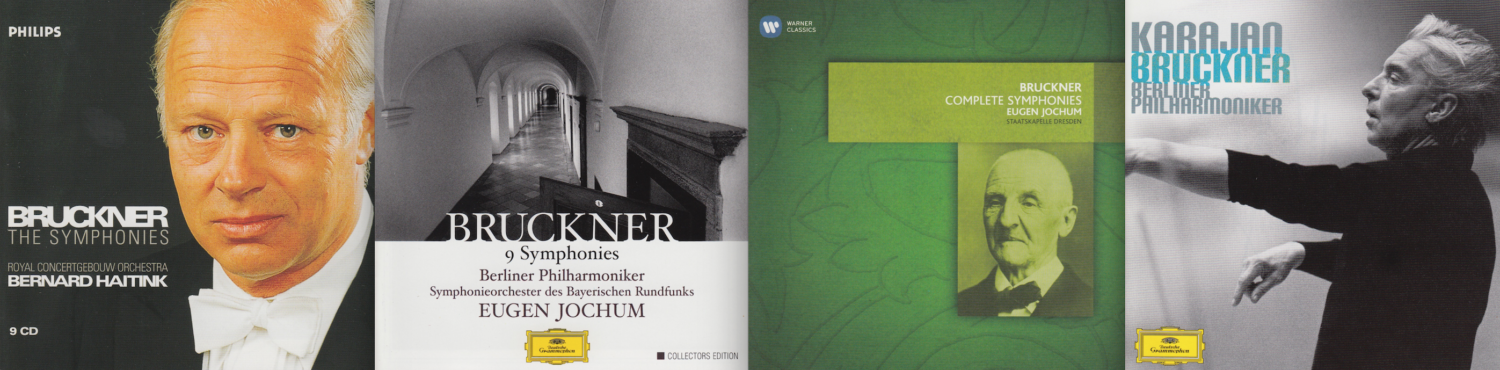

The additional conductors/CD box sets are:

Daniel Barenboim (Staatskapelle Berlin Orchestra)

Daniel Barenboim (Berlin Philharmonic)

Wilhelm Furtwangler

Eliahu Inbal

Marek Jankowski

Otto Klemperer

Simone Young (the only female conductor of Bruckner I’ve discovered)

Two of those sets (Furtwangler and Klemperer) only contain six of Bruckner’s nine symphonies (Symphonies No. 4-9, with 1, 2, and 3 missing). I purposely omitted those box sets for this 144-day project because I wanted to review box sets that were complete, that included all nine.

However, Furtwangler and Klemperer are so historically important that I had to included them in what I’m now calling Phase Two of my Bruckner project.

The inclusion of Furtwangler and Klemperer means Phase Two is 57 days instead of 63 (9 x 6 = 63 – 6 = 57), which is why my next exploration of Bruckner’s nine major symphonies is called 57 More Days With Bruckner And Me.

By the time I’ve completed Phase One and Phase Two, the total number of days to which I listened to a Bruckner symphony will be 201 (144 + 57 = 201).

With the inclusion of these seven additional CD box sets of Bruckner’s symphonies I will be able to say I have truly listened to everything (in CD-box-set form) readily available to the average schlub like me.

That’s a lot of Bruckner, and may even be some kind of record. But of what – some clown sitting in Michigan with the time and money and passion required to pursue this kind of project?

Moving on…

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s unfinished Symphony No. 9 in D Minor WAB 109 (dedicated “to the beloved God”) is Argentine-born pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942-), whom I saw conduct the Staatskapelle Berlin at Carnegie Hall on January 28th of this year. The symphony was Bruckner’s Eighth.

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s unfinished Symphony No. 9 in D Minor WAB 109 (dedicated “to the beloved God”) is Argentine-born pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942-), whom I saw conduct the Staatskapelle Berlin at Carnegie Hall on January 28th of this year. The symphony was Bruckner’s Eighth.

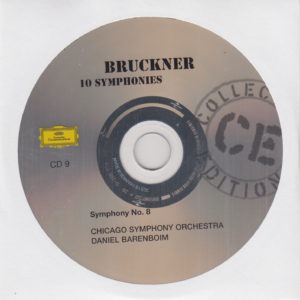

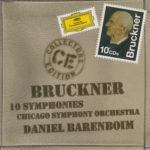

This morning, Maestro Barenboim conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performing Bruckner’s Ninth.

I first heard Maestro Barenboim on Day 1, Symphony No. 1.

Then again on Day 17, Symphony No. 2.

Then again on Day 33, Symphony No. 3.

Then again on Day 49, Symphony No. 4.

Then again on Day 65, Symphony No. 5.

Then again on Day 81, Symphony No. 6.

Then again on Day 97, Symphony No. 7.

Then again, most recently, on Day 113, Symphony No. 8.

Because this is the start of a new symphony, I like to gather as much background information as possible so that I know what I’m hearing.

So, I’ll start with the low-hanging fruit: From its entry on Wikipedia:

Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor is the last symphony upon which he worked, leaving the last movement incomplete at the time of his death in 1896; the symphony was premiered under Ferdinand Löwe in Vienna in 1903. Bruckner dedicated it “to the beloved God” (in German, “dem lieben Gott”).

(While it may seem logical to call this work “Symphony in D minor, opus posthumous”, that usually refers to the Symphony No. 0 in D minor.)

The symphony has four movements, although the fourth is incomplete and fragmentary.

Much material for the finale in full score may have been lost very soon after the composer’s death, and therefore some of the lost sections in full score survived only in two-to-four-stave sketch format. The placement of the Scherzo second, and the key, D minor, are only two elements this work has in common with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

The symphony is so often performed without any sort of finale that some authors describe “the form of this symphony [as] … a massive arch, two slow movements straddling an energetic Scherzo.”

The score calls for three each of flutes, oboes, clarinets in B-flat and A (Adagio only), bassoons, with eight horns (5.–8. Hn. doubling on Wagner tubas), three trumpets in F, three trombones, contrabass tuba, timpani and strings.

Fourth movement

Bruckner had conceived the entire movement; whether the manuscripts he left would have made up the final form of the Finale is debatable. Several bifolios of the emerging autograph score survived, consecutively numbered by Bruckner himself, as well as numerous discarded bifolios and particellos sketches. The surviving manuscripts were all systematically ordered and published in a notable facsimile reprint, edited by J. A. Phillips, in the Bruckner Complete Edition, Vienna.

Because of Bruckner’s individual composing habits, reconstructing the Finale is in some ways easier, and in some ways harder, than it would be to reconstruct an unfinished piece by another composer. Compounding the problem, collectible hunters ransacked Bruckner’s house soon after his death. Sketches for the Finale have been found as far away from Austria as Washington D.C.

Large portions of the movement were almost completely orchestrated, and even some eminent sketches have been found for the coda (the initial crescendo/28 bars, and the progression towards the final cadence, even proceeding into the final tonic pedalpoint/in all 32 bars), but only hearsay suggesting the coda would have integrated themes from all four movements: The Bruckner scholars Max Graf and Max Auer reported that they have actually seen such a sketch when they had access to the manuscripts, at that time in the possession of Franz Schalk. Today such a sketch appears to be lost.

There’s a lot in this article on Wikipedia. If you’re so inclined, I suggest reading it. It’s fascinating, albeit somewhat sad.

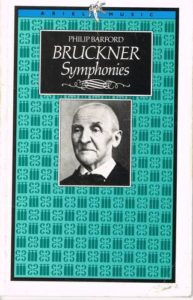

According to the wonderful little book Bruckner Symphonies by Philip Barford (p. 60),

According to the wonderful little book Bruckner Symphonies by Philip Barford (p. 60),

It seems entirely natural and inevitable that Bruckner should have cast his ninth and last symphony in the key of D minor. To lovers of Bruckner’s music, his Unfinished Symphony is a farewell to life, symbolised in the beautiful Adagio, ending in the serenity of the E major with quotations from the Adagio of the Eighth Symphony and the opening arpeggio of the Seventh.

The composer toyed with the idea of using the Te Deum as a finale. This might seem ideologically fitting – it certainly indicates the trend of Bruckner’s mind that he could contemplate such an association between the two works; bit it is not aesthetically sound. The Te Deum is in C major, and thus the wrong key in which to end a symphony in D minor. In any case, the Adagio is wholly acceptable as a finale word. Its closing mood is a fitting benediction on his career.

From its entry on Wikipedia regarding Bruckner’s Ninth,

Symphony No. 9 in D minor

The final accomplishment of Bruckner’s life was to be his Symphony No. 9 in D minor, which he started in August 1887, and which he dedicated “To God the Beloved.” The first three movements were completed by the end of 1894, the Adagio alone taking 18 months to complete, and the final eighteen months of Bruckner’s life devoted to the fourth-movement Finale. Work was delayed by the composer’s poor health and by his compulsion to revise his early symphonies, and by the time of his death in 1896 he had not finished the last movement. The first three movements remained unperformed until their premiere in Vienna (in Ferdinand Löwe’s highly revised version) on 11 February 1903. Bruckner suggested using his Te Deum as a Finale, which would complete the homage to Beethoven’s Ninth symphony (also in D minor). The problem was that the Te Deum is in C major, while the Ninth Symphony is in D minor, and, although Bruckner began sketching a transition from the Adagio key of E major to the triumphant key of C major, he did not pursue the idea. By the time of his death on 11 October 1896, Bruckner had completed most, if not all, of the fourth-movement Finale, with approximately 560 bars in numbered, sequential bifolios in Bruckner’s own hand. There have been several attempts to assemble, augment where necessary and prepare the surviving manuscript material of the Finale for performance. The two most familiar completions are by William Carragan (1983–2010) and by a committee of musicologists, composers and conductors – Nicola Samale, John Philips, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs and Giuseppe Mazzuca (SPCM, 1984–2012).

As I always to, I’ll offer my opinions of the performance at the end of this entry. First, the objective aspects of this recording.

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 in D Minor WAB 109, composed between 1887-1896

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 in D Minor WAB 109, composed between 1887-1896

Daniel Barenboim conducts

Barenboim used the 1894 version (but edited by whom? Nowak? Haas? Carrigan?)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra plays

The symphony clocks in at 60:36

This was recorded at Medinah Temple, Chicago, in May of 1975

Barenboim was 33 when he conducted it

Bruckner was 72 when he died before finishing the Ninth

This recording was released on the Deutsche Grammophon (DG) label

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. He would have this time, too. But he died before completing movement four. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, “Version: 1894”), from this particular conductor (Barenboim) and this particular orchestra (Chicago Symphony Orchestra) is as follows:

I. Feierlich, misterioso (D minor)…………………………………………………………………24:06

II. Scherzo. Bewegt, lebhaft (D minor); Trio. Schnell (F-sharp major)……………………………………………………………………………………………………………11:05

II. Adagio. Langsam, feierlich (E major)………………………………………………………..25:25

IV. Finale. (D minor, incomplete)…………………………………………………………………….0:00

Total running time: 60:36

Okay. I’ve heard from the musicologists and Brucknerians. What say I?

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 4

CD liner notes: 3 (short essay in three languages)

How does this make me feel: 4

This symphony is going to take me awhile to get into.

At first blush, it seems scattered, haphazard, random…and even dissonant. When I first heard these three movements, I thought of John Coltrane‘s Ascension album. It sounded that random to me.

It wasn’t until I listened to Bruckner’s Unfinished Ninth 4-5 times that I finally heard something worth hearing.

I heard the delightful pizzicato opening of the Scherzo which eventually morphed into a rather boisterous movement full of sound and noise and fury.

I heard a truly remarkable Adagio that ends in a delicate, sublime way with the instruments rising and fading into the heavens.

I heard me wanting to hear the fourth movement – even re-created from fragments – just to get a feel for what Bruckner would have done to close a very different symphony from his previous works. (At least, to my ears.)

Actually, no. I am content to hear just what’s there – with that third movement lilting its way skyward, like Bruckner’s spirit had risen to the netherworld above.

I’m still not sold on this symphony. But it’s going to grow on me.