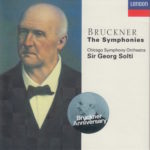

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is Hungarian-born Sir Georg Solti (1912-1997), an artist with a long and noteworthy career. From his entry on Wikipedia:

This morning’s conductor of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (WAB 101) is Hungarian-born Sir Georg Solti (1912-1997), an artist with a long and noteworthy career. From his entry on Wikipedia:

Sir Georg Solti, KBE (21 October 1912 – 5 September 1997) was an orchestral and operatic conductor, best known for his appearances with opera companies in Munich, Frankfurt and London, and as a long-serving music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Born in Budapest, he studied there with Béla Bartók, Leó Weiner and Ernő Dohnányi. In the 1930s, he was a répétiteur at the Hungarian State Opera and worked at the Salzburg Festival for Arturo Toscanini. His career was interrupted by the rise of the Nazis, and being of Jewish background he fled the increasingly restrictive anti-semitic laws in 1938. After conducting a season of Russian ballet in London at the Royal Opera House he found refuge in Switzerland, where he remained during the Second World War. Prohibited from conducting there, he earned a living as a pianist.

Known in his early years for the intensity of his music making, Solti was widely considered to have mellowed as a conductor in later years. He recorded many works two or three times at various stages of his career, and was a prolific recording artist, making more than 250 recordings, including 45 complete opera sets. The most famous of his recordings is probably Decca’s complete set of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, made between 1958 and 1965. Solti’s Ring has twice been voted the greatest recording ever made, in polls for Gramophone magazine in 1999 and the BBC’s Music Magazine in 2012. Solti was repeatedly honoured by the recording industry with awards throughout his career, including a record 32 Grammy Awards as a recording artist.

Another fine biography of Sir Georg can be found here, on the Decca label web site. (Solti’s official web site is gone. The URL points to the Decca label site; however, not to a Solti page. You have to search for Sir Georg’s bio in the drop-down menu.)

Another fine biography of Sir Georg can be found here, on the Decca label web site. (Solti’s official web site is gone. The URL points to the Decca label site; however, not to a Solti page. You have to search for Sir Georg’s bio in the drop-down menu.)

Sir Georg’s passing was covered by The New York Times here.

From the NYT obituary:

More than many of his colleagues, Sir Georg insisted that the precision and bright coloration that could be achieved in the recording studio could be duplicated in the concert hall. Particularly during his Chicago years, he prized a sizzling brass sound and a rich string tone that could be thrilling in Bruckner and Mahler, and that also served him well in Beethoven and Mozart.

More about that below.

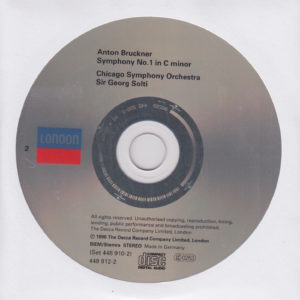

First, the objective aspects to this recording:

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four parts. The time breakdown of this one (Linz version), from this particular conductor (Solti) and this particular orchestra (Chicago Symphony Orchestra) is as follows:

Allegro…………..12:13

Adagio……………13:07

Scherzo……………8:16

Finale……………..13:29

I’ll compare Solti’s interpretation to one from one of my favorite conductors so far: Jochum, from my post on 9 October 2016.

The timing breakdown from the Jochum interpretation (which also used the Linz version) with orchestral performance by Staatskapelle Dresden was:

Allegro…………..12:29

Adagio……………12:38

Scherzo……………9:02

Finale……………..12:57

This tells me the Solti interpretation of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor is only one second longer than Jochum’s. Solti’s Allegro is 16 seconds shorter. His Adagio is 29 seconds longer. His Scherzo is 46 seconds shorter. And his Finale is 32 seconds longer. The total different between the two performances is one second. Solti keeps things moving. But it doesn’t feel hurried. It feels about right.

From the essay (written by Mark Audus) subhead Formal Elements:

Bruckner’s symphonic style is perhaps best expressed as the creative synthesis of the three distinctive sound worlds already identified: church music from the Renaissance to the Classical era, Classical symphonic form (as practised by Beethoven and also Schubert), and the music of Wagner. This synthesis is expressed at all levels of structure, from the smallest motifs and counterpoints to the largest formal elements.

From the subhead Bruckner as symphonic architect:

The spatial metaphor is one repeatedly applied to Bruckner’s symphonies. Most frequent – and appropriate, given the composer’s firm Christian faith – is the analogy of a great cathedral, inside which one might wander around, glancing at different aspects, now distant, no close up, with constantly shifting perspectives on a construction that is nevertheless founded on absolute sureness of design.

Okay. Now, here are the subjective aspects:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 4 (extensive essays about Bruckner and his symphonic style in German, French, English, and what appears to be Portuguese – however, no mention of the record label anywhere in its 56 pages, nor is there adequate information about the version used. Which version isn’t usually mentioned.)

How does this make me feel: 4

Back to the quote from the NY Times above.

I can hear a brassiness in this recording. The Chicago Symphony is known for its robust and noteworthy horn section. I can tell from this recording, which seems to slightly favor the brass instruments – which is an instrument (except for the French horn) that I do not favor.

This emphasis on brass is most striking to me at the end of the first movement. There, the crescendo sounds almost all brass and, truth be told, it kind of grates on me.

However, the swirling, dramatic start to Scherzo (Movement III) is delightful. Yanks me by the labels and pulls me in. I’m hooked. For me, this is the best movement of the four – despite (or, perhaps, because of) the brass instruments.

Overall, this is a fine recording. At times – like in the opening movement – I hang on every note, expecting something remarkable to happen. Sometimes, it kind of does. But not in such a way that I am thrilled or moved deeply.